The new-found stone created some stir among runologists

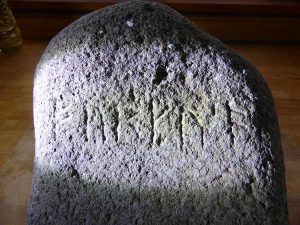

The Eigg Runestone. Photo: Camille Dressler.

Late last year, a runic boulder was found by a resident on the island of Eigg, part of the Inner Hebrides. Eigg has an ancient history, showing settlement by both Gaelic and Norse people. It was a Viking habitation and a base for their trade with Ireland a thousand years ago. Parts of a Viking ship have also been found here, so it would not be impossible for a runic inscription to be discovered on the island. After all, there is an authentic runic grave slab on Iona not far south of Eigg, and a runic cross from Kilbar on Isle of Barra not far to the northwest.

The new-found stone created some stir among runologists, it appeared before Christmas in a local newspaper, the word spread and the other day a journalist scooped it for The Telegraph. The article describes the debate among laymen and runologists on whether the stone is authentic or modern, and what it really says. This, of course, is the most important piece of evidence. The first reading was furku.al or furkusal, neither of which is recognizable linguistically.

“Having done a bit of stone carving myself in my time”, she continues “I can assure you it is not a stone which is easy to carve by any means!”

Britain’s leading runologist, Prof. Michael Barnes, quickly established the correct reading, furkuson, which he thought could be a rendering of the Gaelic last name Farquharson. The inscription might instead be read furguson since there may be a dot in the pocket of the k (half way between the tips of the staff and the twig), turning it into a g-rune. A field runologist will have to confirm or reject that when examining the inscription. Anyone familiar with Viking runes would know that k was used for both k and g, so the name is likely Furguson either way.

Furguson, the son of Furgus (derived from Gaelic Fearghus) can also be spelled as Ferguson or Farguson, for example. People named Ferguson can be referred to as Furguson, as is the case with Duncan Ferguson who inhabited the house for a time where the new runestone was found, but who knows nothing about its origin. His family members have been the only Fergusons on Eigg for the past century or more, according to Camille Dressler, chair of the Eigg History Society. She also reports that the monument consists of “a block of columnar basalt – a very common stone on Eigg”. “Having done a bit of stone carving myself in my time”, she continues “I can assure you it is not a stone which is easy to carve by any means!”

So, the question remains: Is the Eigg stone from the Viking Age or is it modern, probably carved in the last hundred years? Michael Barnes advances a number of reasons why the inscription is not likely ancient:

- It runs horizontally; very, very few Viking-Age and medieval inscriptions are set out in this way.

- It does not conform to any kind of inscription we know; given the brevity of the text the most likely explanation would be a Norse name (as on Holy Island), but I cannot find anything remotely resembling such in these runes. Nor is the Eigg inscription of memorial type.

- The inscription has no obvious purpose; it looks to be more than a casual graffito, in that one would think the stone was set up in order to bear the inscription (unless evidence can be produced to the contrary); but then one would expect either a memorial or perhaps a boundary marker – which the runes do not suggest (cf. above).

Barnes concludes: “If my thought be accepted, we have a parallel in the kiorki younk (i.e. ‘George Young’) inscription from Bracadale, Skye.” My own conclusion certainly support that of Michael Barnes’. Just having a personal name on a runestone is possible, but never just a last name as in this case. Also, like Michael Barnes I cannot find any Viking name or even word that could hide under the runes furku(son). Finally, the shape of the r-rune is unexpected.

That we cannot (yet) identify the actual carver does not by itself show an ancient origin.

Science deals in probability, not possibility. That we cannot (yet) identify the actual carver does not by itself show an ancient origin. As very little speaks in favor of the Eigg stone being a Viking Age inscription the probability is that it stems from the last century or so. This may disappoint some, but should surprise nobody. Runic inscriptions are constantly produced in our times, as proven by the Bracadale inscription just mentioned. Michael Barnes in his Runes: A Handbook (2012) mentions a number of modern inscriptions in Britain, Scandinavia and the United States (pp. 135-142). Last year Martin Findell published another recent inscription from Portormin Harbour in Dunbeath, Caithness, found in 1996.

Note: My thanks go to John Borland who notified me of the Eigg stone, Michael Barnes for allowing me to quote him, and Camille Dressler for much valuable information as well as for the permission to use her picture of the runestone.

It is very difficult to analize a runescript from a photo, and here it seems the last rune isn’t even included.

However, I am not convinced of the ….son translation. I can only see an A as the last one of the photo. Expect there must be an L after that, for the first translation to be offered.

Now if you take the short twig runes, the Rök runes, then the first rune can be read as a B. This gives a different word. Something like : burkusal.

And why do you assume it being written by a Scot? It might be written by a Viking, hence take another look at the possible meanings in the old Norse, of which I am sadly no expert.

As to the question of its age, it should be possible to make some scientific tests to make an assumption of its age, from the weathering. Or dig into the history of its place of discovery. I aggree, it could well be ‘modern’, from the looks of it.

Looking forward to more insight.

We have also had access to a drawing of the inscription, making clear the shape of the last rune. On the second last rune the staff continues above the upper twig, making it an o-rune rather than a pre-Viking or very early Viking Age a-rune which would no co-occur with a short-twig s-rune. I am thus fairly confident of the reading, even though the stone needs to be examined by a professional runologist before we can be completely certain.

Almost anyone could have carved the Eigg stone, I suppose, but not a Viking if it is modern. Both Michael Barnes and I have tried to find a possible meaning for the text in Old Norse, without success. Since the inscription makes good sense as a modern last name, that is another indication of its age.

Weathering is not a good method of dating stone surfaces. Several instances of weathered runestones where surface wear and patina was taken to indicate an ancient origin have turned out to be carved in recent decades.

Henrik

Pingback: Litewskie runy ujawnione: Norweski lingwista mówi, że Bałtowie mieli kalendarze runiczne | /|