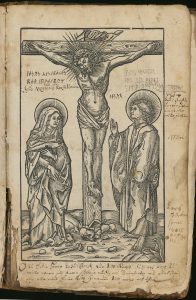

Thet Nyia Testamentit på Swensko (1526). Pag. 2:LXXIXr of the Uppsala University Library copy Sv. Rar. fol. 10:23a. Photo: Uppsala University Library (Public Domain)

Lately, I have branched out to become interested in such a modern(!) topic as the first translations of the Bible into different European vernaculars

This blog must give the impression that runes are all I care about. Strictly speaking, this is not true as I have other interests, as well. Old Scandinavian philology is a fascinating topic, for example, as are names, especially personal names of all kinds.

Lately, I have branched out to become interested in such a modern(!) topic as the first translations of the Bible into different European vernaculars. In England and the United States the King James Version from 1611/1769 is a hotly debated subject, and millions of people, primarily in America, still read this old and beautiful translation.

In seven years we will have the 500-year anniversary of the first full translation of the New Testament into Swedish. Thet Nyia Testamentit på Swensko was published in 1526, incidentally the same year as the first English translation by William Tyndale.

Runes are never mentioned in the Bible, at least not in the original Hebrew, Aramaic or Greek versions

Runes might seem to have little to do with Bibles as the two phenomena originated in different regions, although we have reason to believe that the runic characters were invented at the time as the youngest books in the Bible were written, around 100 AD. But runes are never mentioned in the Bible, at least not in the original Hebrew, Aramaic or Greek versions.

If you turn to the Icelandic translation, however, you do actually find at least the word rune used, although only twice and that in the apocryphal/deuterocanonical book Ecclesiasticus. In chapter 39, verse 3 we find Hann ræður rúnir spakmæla (King James Version: “He will seek out the secrets of grave sentences”) and in 42:18 ræður þær rúnir sem stýra heimsrás (King James: “he beholdeth the signs of the world”).

Nyia Testamentit is perhaps the most influential book ever published in Sweden

But let us return to Nyia Testamentit. This is perhaps the most influential book ever published in Sweden. For the first time ever the same text was available in every parish church all over the country. It was printed in a couple of thousand copies and the biblical text had the highest status possible. 167 times each year for almost two centuries the same passages were read out at the divine services. Standard Swedish as we know it would not exist without this translation.

The University Library at Uppsala University holds four copies of the translation, and in Alvin, the Library’s platform for digital collections and digitized cultural heritage, we are fortunate to have the only digitized copy (of at least 18 surviving), the one with the shelf mark Sv. Rar. fol. 10:23.

So, what does this have to do with runes?

So, what does this have to do with runes? Well, in one of the other three copies held by the University Library, Sv. Rar. fol. 10:23a, the final page in fact bears runes, on both sides.

On the recto side of the page (see picture at the top of this page), with a crucifixion scene, we see iesus spelled out to the right of Christ and iesus nasarenus rex iudeorum over his mother, Mary. The latter is followed by “thet är Jesus Nazarenus Rex Judeorum” (‘that is Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews’).

So far no great surprise, although the x-rune has a shape usually used for e. The ring-shaped version of the latter rune is rare but does occur here and there, as Alessandro Palumbo showed in his dissertation (note 43). All-in-all the runes have a medieval style and may not be much younger than the book they are written in, although the rune å certainly proves this to be a post-reformation runic script.

This is where it gets exciting

Over the apostle John we find iesus christus her uår helsa som os ala uille frelsa in another hand, also with a transcription “thet är Jesus Christus är wår helsa som oβ alle wille frälβa” (‘that is Jesus Christ is our health who us all would save’). This is where it gets exciting. We get here the first lines of a well-known hymn, known in English as Jesus Christ, our blessed Savior. The first stanza reads in one version:

Jesus Christ, our blessed Savior,

Turned away God’s wrath forever;

By his bitter grief and woe

He saved us from the evil foe.

The text itself is a reworking by Martin Luther of a medieval hymn. It was first published in German in 1524 as Jesus Christus, unser Heiland, der von uns den Gotteszorn wandt and in Swedish in 1530 and 1536.

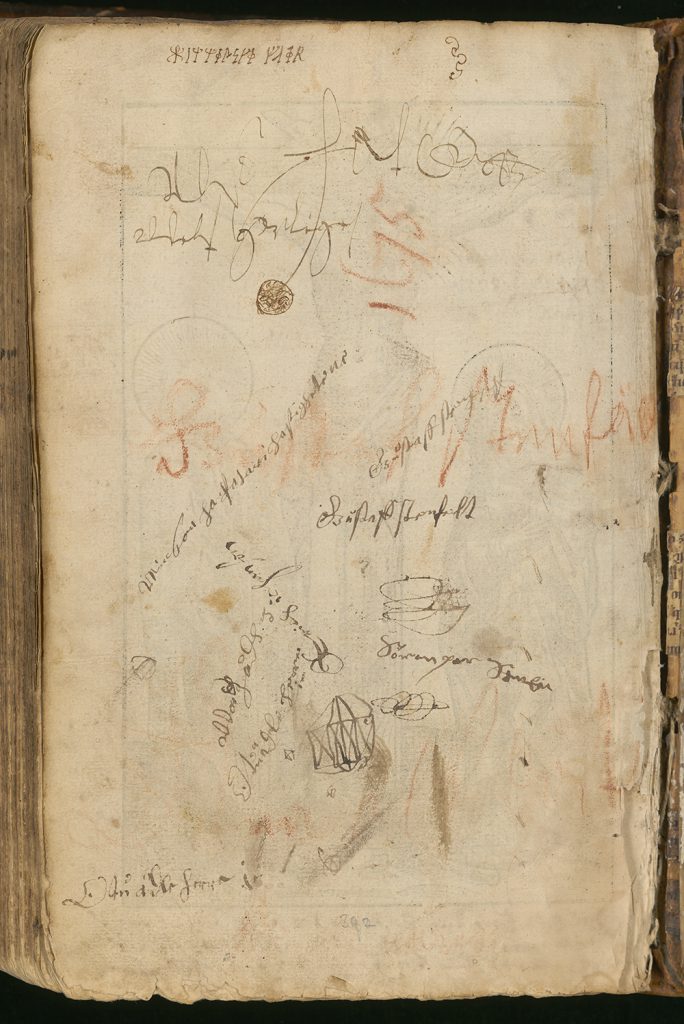

Thet Nyia Testamentit på Swensko (1526). Pag. 2:LXXIXv of the Uppsala University Library copy Sv. Rar. fol. 10:23a. Photo: Uppsala University Library (Public Domain)

It is difficult to date the runic scribblings

On the back of the page we find himmelske fad͡er (‘Heavenly Father’) with the same runes as in the hymn quote, although the bindrune d͡e is uncertain. It is difficult to date the runic scribblings, and it is uncertain if all the related texts are written at the same time. I am no expert in Early Modern handwriting, but the roman writing seems later than the 16th century, whereas the runes could be older at least in part. We need a study of runic inscriptions from after the Middle Ages; there is obviously a lot to be discovered here.

We will probably never know why someone chose to write with runes in a copy of Nyia Testamentit, nor who this person was. Sweden’s equivalent of Martin Luther was Olaus Petri, the translator of the hymn and a person also versed in runes according to Upplands runinskrifter (p. 74). He has also been claimed to be involved in the translation and production of Sweden’s first New Testament. Perhaps the runes found in the Uppsala University Library copy have something to do with him?

This is amazing. How would one write Christ is Risen in runes?

That depends on the language and the type of runes one wants to use. Take your pick!