The Guggenheim Museum in New York City recently held the first major solo exhibition in the United States of Swedish painter Hilma af Klint (1862–1944). Af Klint transformed herself in a few short years from being a traditional 19th century painter to creating some of the most original artwork of the 20th century, the first abstractions in modern western art.

Born and educated in Stockholm, af Klint was trained and worked as an artist in landscape, portraiture, botanical and veterinary illustration. At the same time in her personal life she was exploring Spiritualism, Rosicrucian practice and Theosophy, which embodied Hindu and Buddhist teachings, Western occult practices, and theories of evolution.

Af Klint sought to create a new visual lexicon to embody her understandings of spiritualism, science, nature and art.

About af Klint’s eclectic curiosity, curator Elizabeth Finch writes, “Af Klint owned the 1895 Swedish edition of [Theosophical Society founder Helena Blavatsky’s] ‘The Secret Doctrine’ and shared Blavatsky’s talent for scouring all spiritual, religious and intellectual sources for evidence of the progress toward transcendence. Anything that fit af Klint’s worldview could be included within her personal spiritual synthesis”. [1]

From 1906 to 1908, af Klint created artwork based on images she received in séances from spirits, her etheric mentors. Moderna Museet curator Iris Müller-Westermann explains, “Hilma af Klint was asked by the ‘higher masters’ — as she called them — whether she would agree to bring down images from higher realms of consciousness to a physical plane […] the first 111 paintings came into being between November 1906–April 1908. [—] The cycle Paintings for the Temple looks like nothing else produced in Sweden at that time the images are filled with symbols, letters, geometric forms, and sometimes also figurative elements.” [2]

Af Klint sought to create a new visual lexicon to embody her understandings of spiritualism, science, nature and art. As art historian Julia Voss writes, “The resources and methods of classical painting no longer sufficed for what she wanted to depict on canvas. Art itself needed to undergo an evolution […] she decided to create a world of visual form to which she would repeatedly return.” [3]

I believe af Klint’s early visual vocabulary was heavily influenced by the ancient rune stones in her environment

Everything comes from somewhere. Even etheric mentors need to start somewhere. I believe af Klint’s early visual vocabulary was heavily influenced by the ancient rune stones in her environment. Particularly in her seminal abstract work between 1906 and 1908, there appear to be visual motifs from rune stone carvings, from Gotland picture stones dating from ca 400–600 AD to Viking age stones from 750–1100 AD. As af Klint sought to develop a new visual language, it makes sense she might play with symbols and shapes in the ancient rune stones found throughout the countryside in Uppland where she lived and traveled. The pictures on rune stones were pictures from her own history, from a time where religious beliefs were shifting and not solidified, pictures from a time which has left so little evidence of itself that it was, and remains, a mystery in many ways. These mysterious symbols and forms were ripe for a modern artist to infuse with new meaning.

Geometric precision was not a value with the rune stone carvers

The ancient rune stone carvers embraced a free flowing use of symbols and imagery, Christian crosses, figures from Norse mythology, spirals, double spirals, flower shapes, dogs, horses, beasts with human heads, round sun symbols rolling across the sky. Geometric precision was not a value with the rune stone carvers. Rather, the carvers often appear to follow the organic logic of their stone’s shape, with its irregular curving edges and wavy surfaces.

Runestone U 212 in Vallentuna. Cross with flower shape at center, snakes coming from base, connected by a ligature. Photo: Marco Bianchi (CC BY).

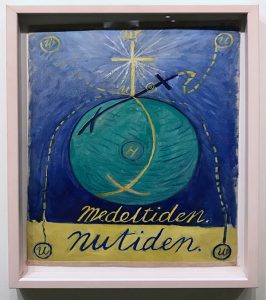

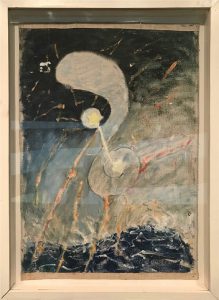

Hilma af Klint, Primordial Chaos, No. 12, 1906–07. Cross with flower shape at center, snakes coming from base. Letters/words inside and outside snake shapes. “Medeltiden” (Middle Ages) and “Nutiden” (The Present). Photo: Sue Carlson.

Snakes are ubiquitous in Viking Age carvings. We often see them circumnavigating the edge of the oval-shaped stones. They weave over themselves and morph into sperm-like creatures with long thin tails and heads or S shaped curves ending in knobs (see, e.g., the Ölsta rune stone below). Another visual motif in the ancient carvings is a Christian cross with flowerlike shapes emanating from the center and snakelike forms coming out of or around its base, often curving up toward the top or winding along the circumference of the stone. Sometimes two snakelike shapes are connected by a ligature, a visually organizing element which serves to ground the image and keep the curvilinear bands from seeming to drift away (e.g. U 212 in Vallentuna) .

The early rune carvers felt written language was inherently mysterious

And then there are the rune letters. Swedish rune researcher Sven B.F. Jansson wrote, “In very early times the runes were regarded as a gift from the gods. In Scandinavia as elsewhere, the mysterious act of giving permanent form to ephemeral speech was ascribed to divine intervention. [—] According to Norse belief, it was Odin who discovered these mystic, potent signs.” [4] The early rune carvers felt written language was inherently mysterious, which makes logical sense. Writing is mysterious in that it defies the laws of the physical world. Instead of spoken language being limited to those who speak it and those within earshot who hear it, written language can take the sound of a word, and its meaning, freeze it on a stone, secure it to a physical place, and send it into the future. The rune stone carvers were artist/writers, using text and pictures to convey meaning. For the rune stone carvers, writing becomes an integral visual component of the picture itself.

In runic writing, creative play was not hindered by convention or authority

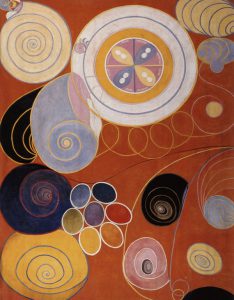

Hilma af Klint, Group IV, The Ten Largest, No. 3, Youth 1907. Sun symbols and spirals. Photo: Sue Carlson.

Viking Age text carved in stone was written in Old Norse, with rune letters in an alphabet known as the futhark. The futhark never became a fully mature writing system. Spelling was not systematic, there were no upper and lower case letters to indicate a word’s role in a sentence. Often the rune writing looks like a long series of letters with no indication of where individual words start and end. Creative play was not hindered by convention or authority. Rune letters were written in sentences forward and sometimes backward, sometimes in code. Sometimes rune carvers used a cipher game to write texts, where a number of slash marks stood for a letter’s place in the order of the “alphabet”. Letters might appear within winding bands, or floating beside a picture, either horizontally or vertically. Letters and words could be intentionally cryptic and stand for other meanings.

In her seminal abstract work from 1906 to 1908, Hilma af Klint draws and paints shapes that look like elements from Viking Age rune stone carvings. Julia Voss describes af Klint’s early work, “Right from the start, a recurrent motif was the spiral […] rolls like a ball lightning towards the viewer.” [5] This description also fits the picture stones from Gotland, likely displayed in the Swedish History Museum’s collection, which in 1906 was housed in the Nationalmuseum building, just blocks from af Klint’s art studio at Hamngatan 5 in Stockholm. “The Ten Largest”, contain spiral shapes and sunlike shapes, floating in the painting, similar to the Gotland picture stones.

Af Klint’s works are full of curved lines weaving in and out of themselves

Ölsta rune stone in Uppland (U 871). Red S-curves with knobs; white sperm-like creatures with heads and eyes. Photo: Sue Carlson.

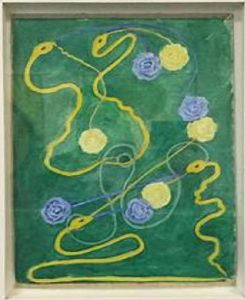

Hilma af Klint, Group 1, Primordial Chaos, No. 13, 1906. Sperm-like creatures with heads and eyes. Photo: Sue Carlson.

Af Klint’s works are full of curved lines weaving in and out of themselves, morphing into shapes similar to the Viking Age carvings, sperm-like creatures (see Primordial Chaos, No. 13, photo to the left), S-curves ending in knobs (see Primordial Chaos, No 13, photo below), spirals and double spirals. There are snakes which curve around the edge of a picture, and other kinds of animals and plant like images. There are crosses which seem to reference Christianity, but are woven into pictures which include other symbols of ambiguous origin. Af Klint’s early abstract images are often flat and cartoon-like, similar to the pictures on runestones, which, possibly because of the challenges of carving in stone, lack detailed rendering.

The Viking Age configuration of a cross with flower shapes and snakes appears to have directly inspired af Klint in Group 1, Primordial Chaos, No. 12 (see photo above). As in the Viking carvings, a cross has shapes emanating from its center, snake-like creatures coming out of its base, and letters and words both in and outside snake forms. Af Klint may have even provided textual evidence of her work’s relationship to Viking Age carving. In Swedish, she labels the top part of the picture “Medeltiden” (Middle Ages) and the bottom part “Nutiden” (The Present). Here she may be telling us exactly where she is getting her imagery.

Hilma af Klint created works which integrated art and written language into a visual experience

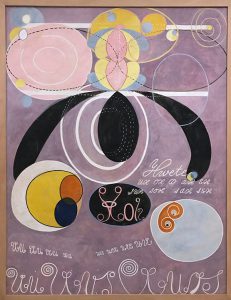

Hilma af Klint, The Ten Largest, No. 6, Adulthood, 1907. Writing as pictorial component. Photo: Sue Carlson.

Hilma af Klint was an artist/writer, and like the Viking stone carvers, she created works which integrated art and written language into a visual experience as in The Ten Largest, No. 6. Did she know that Viking rune words and letters were sometimes written in systems of ciphers or intentionally cryptic? I’m not sure. But the rune letters must have looked cryptic, i.e. difficult to decipher. Af Klint’s notebook titled Letters and Words Pertaining to Works by Hilma af Klint, is an elaborate guide to the hundreds of phrases, words and letters found throughout her visual work. Müller-Westermann explains, “Letters and Words describes a complex system of language crucial to a body of visual work- an integration of language and art that is unique within its time.” [6] Integration of language and art is also unique in the Viking stones.

Integration of language and art is also unique in the Viking stones

I can’t prove that Hilma af Klint saw or loved the rune stones (although further research might illuminate). I don’t know if she visited the Swedish History Museum and saw rune carvings displayed there. I don’t know if she read the texts of the time which discussed rune stones. But she lived nearly her whole life in Stockholm and Uppland, sometimes on islands in Lake Mälaren, the Adelsö Forest, Engelsberg, Uppsala. She lived in and around the epicenter of Viking Age runestones, with over 2000 carved stones found in this area, the heaviest concentration on the planet. What I see is a shared visual lexicon between the rune stones and af Klint’s earliest abstract work.

Julia Voss goes on to describe af Klint’s compositions “Throughout all these transmutations and metamorphoses, the art of af Klint lets forms, outlines and shapes resonate like echoes without remaining focused on a single quotation. The world of her creative activity is itself in a process of evolution. In constant variations she invents intermediate forms of each element, with flowing transitions between abstraction, symbol, sign and letter. The flow of images is an intoxicating mix, revealing the free play of life forces: moving, melting, joining; turning, inseminating, growing: flowering, playing, mating.” [7] These words can also describe the tremendous inventive play of the Viking rune stone carvers. Perhaps af Klint captured that inventive spirit and brought it, centuries later, into another time.

References

[1] Elizabeth Finch with Catherine de Zegher and Hendel Teicher (ed.) p 97, 3 X Abstraction, Yale University Press, and Drawing Center, New York, 2005

[2] Iris Muller-Westermann with Kurt Almqvist and Louise Belfrage (ed.) p 185, Hilma af Klint, The Art of Seeing the Invisible, Axel and Margaret Ax:son Johnson Foundation, 2015

[3] Julia Voss with Emma Enderby (ed.), p 25, Hilma af Klint, Painting the Unseen, Koenig Books, London, 2016

[4] Sven F. Jansson, p 9, Runes in Sweden, Gidlunds, 1987

[5] Voss, p 25

[6] Iris Muller-Westermann, p 246, Hilma af Klint : Notes and Methods, Christine Burgin/ University of Chicago Press, 2018

[7] Voss, p 28

The author

This month’s Rune Blog is written by guest blogger Sue Carlson. She is an artist in New York and takes a keen interest in things runic. She has Swedish roots, family in Minnesota and has attended Runic tour lectures in Minneapolis, as well as participated in the yearly Rune Rounds to Sweden. She is also a recurrent donor to Uppsala Runic Forum.

Coincidentally, this documentary about Hilda af Klint is making the rounds of film festivals this year: