The documentary evidence for the runic inscription is slim in the extreme. In fact we only have a fourth-hand version of the putative text

The Runestone on Martha’s Vineyard in Massachusetts is one of the least known and certainly least discussed of all potential runestones in North America, yet its story is one of the most entertaining of all. The documentary evidence for the runic inscription is slim in the extreme, in fact we only have a fourth-hand version of the putative text. Ideally, a runologist wants to study a runic message first hand, since many details in the original are decisive when determining age and intended meaning. For the inscription discussed here this is clearly not possible and might, I fear, never be.

Our only source of information regarding the runestone in question is a 1949 journal article by Hjalmar Holand, of Kensington Runestone fame. In 1946 Holand had received through an intermediary, W. H. Thoreson, a copy of a runic inscription from a man named Godfrey Priester, who in turn had reproduced it from a drawing made by John (of unknown last name), an employee of his. This hired man John “was a Slavic immigrant from the province of Ruthenia” (now in western Ukraine). Priester inhabited a summer home situated on a property near North Tisbury on the island of Martha’s Vineyard in the state of Massachusetts.

Our only source of information regarding the runestone in question is a 1949 journal article by Hjalmar Holand

In 1922 John did some work in the woods and came across a small boulder (or a rock sticking up only a little bit from the ground) with an inscription, which he copied on “a small piece of wrapping paper”. Mr. Priester meant to investigate the matter but was too busy and forgot all about it until he was visited by Mr. Thoreson in the summer of 1946. They came to talk about the history of Martha’s Vineyard when Priester remembered the runic drawing:

“He spent several days in looking for the copy and finally discovered it among some old papers in the attic. Upon examining it, Mr. Thoreson said he believed it was the copy of a runic inscription such as he had seen in Denmark. This revived Mr. Priester’s interest, and the two men set out at five o’clock the next morning to find the stone.”

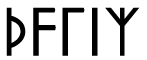

They lost their way, however, wandered for hours and never found any runic boulder. Thoreson got a copy of John’s wrapping paper drawing, and eventually Holand received a facsimile of Thoreson’s copy. In Holand’s article the runic inscription is reproduced in the following manner:

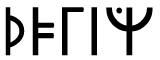

Holand “corrects” this to:

Holand “corrects” this to:

He is obviously much influenced by his experience with the Kensington inscription, since his “corrected” runes are of the Kensington type. Nevertheless, I don’t think this monument inspired the one from Martha’s Vineyard, far from it.

One might think that the only way of testing the authenticity of the runes being discussed would be to locate the boulder found in 1922. Unfortunately, it has never been seen or at least reported since, even though Holand writes hopefully that it is “perhaps only temporarily lost”. This is a special case, however, and the key to the mystery was held already by Mr. Thoreson in 1946. He observed, we remember, that he “believed it was the copy of a runic inscription such as he had seen in Denmark”.

There are no “proper” Danish runestones that ancient.

There are no “proper” Danish runestones that ancient. Norway has most of the oldest runestones and among them was once one from Bratsberg. It was discovered in the first decade of the 19th century but sadly soon lost, built into a stone wall and never located since.

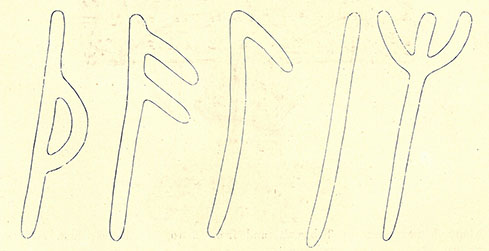

Fortunately a rubbing was taken in 1806, now preserved at the National Museum in Copenhagen. This is a very high quality impression of an inscription made by putting a paper on the stone surface, rubbing it with a crayon, and then tracing the outline of the white spaces where the grooves of the runes become visible. There were also two independent drawings made of the stone. All accounts agree: the inscription reads ᚦᚨᛚᛁᛘ, probably a man’s name Þalliz (Þ is pronounced as th).

The runes on the Martha’s Vineyard stone must surely be modeled on the one from Bratsberg

The Bratsberg Stone also appears 1867–68 in the first volume of the colossal work Old-Northern Runic Monuments of Scandinavia and England by George Stephens and in Sophus Bugge’s corpus of the oldest runic inscriptions in Norway (1891–1903). The early inscriptions make up a very small portion of the 7000 now known altogether, only 7 %. The chance that one of these texts would have an independent twin in America is truly incredible, and the runes on the Martha’s Vineyard stone must surely be modeled on the one from Bratsberg.

Scandinavians first landed in North America around the year 1000, and perhaps some of them made it to Massachusetts. But even if so, they could not have carved the runestone at North Tisbury since the runic characters had changed in shape and use since the time of the Bratsberg stone. Especially the last of its runes prove this. Its shape m and value z had changed to z and ʀ or y, respectively, long before the Northmen’s visit.

The logical conclusion is that there really was an inscription at North Tisbury

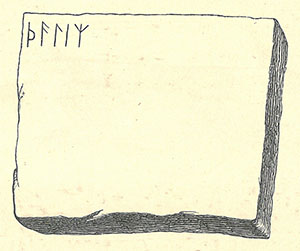

Klüwer’s drawing of the Bratsberg inscription from 1823. Printed in George Stephens’ “Handbook of the Old-Northern Runic Monuments of Scandinavia and England” (1884)

We need to look for an different explanation. Could Godfrey Priester or Mr. Thoreson have mistaken a copy of the Bratsberg stone for the runes on the wrapping paper? It seems highly unlikely, I would say impossible. Nor is there reason to believe that any of the persons involved tried to perpetrate a fraud. The logical conclusion is that there really was an inscription at North Tisbury, conscientiously depicted by the hired man John. But how did it get there?

But how did it get there?

Since it is virtually identical to the Bratsberg inscription, it has to derive from it in some way. No one in America is likely to have seen the original, and the information in Stephens’s or Bugge’s expensive and scholarly editions offer no reason why anyone would copy the inscription from there. But it was also available in Stephens’s popular and more readily available Handbook of the Old-Northern Runic Monuments of Scandinavia and England from 1884, where reproductions of both the drawing and the rubbing are given (see surrounding figures).

M.F. Arends rubbing of the Bratsberg inscription from 1806. Printed in George Stephens’ “Handbook of the Old-Northern Runic Monuments of Scandinavia and England” (1884)

The only noteworthy difference between these facsimiles and the runes as rendered in Holand’s article is that the second and third runes on the North Tisbury Runestone have horizontal branches instead of diagonal, but they could well have been copied that way by someone not realizing that slanting branches are of some runological significance.

In his Handbook, Stephens offers a new and interesting interpretation of the runes, as a (non-existent) woman’s name, Þælia. Although Stephens is wrong, his suggestion corresponds to Thalia and visually looks like Dalia or Delia (æ/ae can be pronounced as e in be, cf. aeon). These are all women’s names used in many countries, including the United States.

whoever was responsible for the rune carving probably had access to the Handbook

My guess is that a person before 1922 (but in modern time) wished to write one of these names in runes on a stone. Perhaps it was someone admiring a woman called Thalia, Dalia or Delia. Maybe it was the woman herself who wished to immortalize her name. If so, she succeeded, but we will probably never know the true story. But whoever was responsible for the rune carving probably had access to the Handbook and discovered in it the Bratsberg inscription with Stephens’s (incorrect) reading and interpretation. Struck by the similarity to a woman’s name that the reader wished to commemorate, the runes made their ways from the printed page onto a boulder in the backwoods of a Massachusetts island.

This runestone has played very little role in the discussion of runic inscriptions in America. Except for an occasional mention on the Internet, I have found no sources dealing with it other than the Holand article. Yet there are threads worth following up. Do the original wrapping paper drawing or any of its copies still exist? It would be valuable to compare them to the suggested model, the Bratsberg inscription. But most importantly: Is the runestone on Martha’s Island still out there in the woods on the land once owned by Godfrey Priester?

Note: There are two further possibly runic inscriptions from the island, at Oak Bluffs and at Aquinnah. The monument discussed above should be called the North Tisbury Runestone and not the Martha’s Vineyard Stone.

The stone is just below the tides, covered with seaweed.

My family used to boat there, great stripe bass fishing and Blue fish. The DEM keeps people off of the island.

A.C.Cloutier

Westport,MA